As intended, the readings this week have been provoking some good discussion, especially the Robins and Webster piece. Over at

Directions for the Information Superhighway", Amanda wrote,

This piece has a little of that "1984" or "Brave New World" vibe with all the talk of social control and government management. They discuss a conception of the information age as unequal access to and control over the info resources. I'm not sure I agree entirely--clearly there are some very egalitarian information sources available today (MOST web content, social networks, Wikipedia, access to blogs, access to world news, even international libraries, in some cases...)

Similarly, in

J676: Mike's Musings, Mike questioned whether Robins and Webster were too pessimistic in their critique:

Robins and Webster ignore the recent Internet developments that allow individuals to produce and share content on a global scale. This piece was written in 1999. If Robins and Webster were writing today, they would have to acknowledge the community-building and personal-publishing advances that have become available. [...]

Today%u2019s world isn%u2019t quite the corporation-controlled desert the authors describe. For example, for every new feature that Google produces, thousands of people criticize it. For every product that Steve Jobs comes out with, thousands of consumers critique it. [...]

The grand collection and systematic organization of information by those in power can have a numbing effect on the %u201Clittle guy%u201D, but the sharing of information on a global scale can return at least a small portion of that power back%u2026 a portion that seems to be growing every day.

This is tricky though, because unlike, say, the Roszak piece, I think Robins and Webster are arguing that the development of cyberspace is neither utopian nor dystopian, but contradictory. After all, even though they argue that their purpose is "to explore this dark underside of the Information Revolution," they admit that "serious, rather than just well-meaning, responses are only possible if we confront, not just the repressive potential of information and knowledge, but more significantly the integral and necessary relation between repressive and possible emancipatory dimensions." [66] In other words, there is a "dialectical" (intimately interrelated but often necessarily oppositional) relationship between the good things we as consumers, citizens, and cultural animals want cyberspace to provide, and the risks which result from the way that states and markets end up providing those thiings.

Further thoughts?

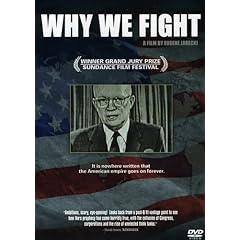

For anyone interested in learning a little more about the American Military-Industrial Complex, I'd recommend the recent documentary Why We Fight. Released in 2005, the film uses Eisenhower's parting address as the centerpiece of a more involved look at the complicated relationship between researchers, workers, corporations, the military, and politicians from WWII to the present. It's definitely worth watching regardless of your politics.

For anyone interested in learning a little more about the American Military-Industrial Complex, I'd recommend the recent documentary Why We Fight. Released in 2005, the film uses Eisenhower's parting address as the centerpiece of a more involved look at the complicated relationship between researchers, workers, corporations, the military, and politicians from WWII to the present. It's definitely worth watching regardless of your politics. For anyone who's looking for a little more information on

For anyone who's looking for a little more information on